Receptive Language Baby Understanding language babies Infant

Guide for Helping Babies

Understand Language

Receptive communication is the ability to receive and understand a message from another person. When babies are listening, they turn their head toward your voice, and will then respond to simple directions, often with vocalizations. Early on, these vocalizations will just be sounds, but as baby approaches their first birthday, they will begin to use meaningful language.

Understanding words and sentences Understanding language concepts, like prepositions ( on/in ) and size ( big/small ) Listening to and interpreting a story or conversation Following simple and multi-step instructions, like “ Pick up the ball and bring it to me ” Answering questions accurately Using correct pronouns and tenses

Free Printable Speech Language Brochure

from Pathways

Supporting language for the first year

Supporting Language and Literacy Skills from 0-12 Months

The idea of babies and toddlers talking and reading can seem incredible, but language and literacy skills start early—before birth. Learn how you can support these skills from 0-12 months.

Watching your baby and learning how she communicates through sounds, facial expressions, and gestures are all important ways to help her learn about language and the written word.

It isn’t necessary to “teach” very young children. Formal classes and other activities that push babies and toddlers to read and write words do not help their development or make the do better in school. In fact, they can even make children feel like failures when they are pushed to do something they don’t enjoy or that is beyond their skills.

Early language and literacy skills are learned best through everyday moments with your child—reading books, talking, laughing and playing together. Children learn language when you talk to them and they communicate back to you, and by hearing stories read and songs sung aloud. Children develop early literacy skills when you give them the chance to play with and explore books and other written materials like magazines, newspapers, take-out menus, markers, and crayons.

Language and literacy, while two different skills, build on one another in important ways.

FrequentlyAsked

Questions

What can I expect from my 4-month-old when it comes to reading books with her?

Literacy is a process that builds over time, with each new skill adding to the one before. Keep in mind, though, that literacy is not just a skill, it is also a love—a love of books and the magic they offer.

Below are some general guidelines about how children play with books from birth to age 3:

0-6 months: May calm down while a familiar story or rhyme is read.

6-8 months: May begin to explore books by looking, touching and mouthing. May seem fascinated by a particularly bright picture.

9-11 months: May have a favorite picture—for example of a smiling baby or a familiar-looking object.

12-18 months: May begin turning pages or holding a book as if she is “reading.” May begin saying the word “book” and/or showing a preference for a specific book at bedtime.

24-36 months: May begin anticipating the story. For example, while reading Goldilocks and the Three Bears, your toddler may say, “Just right!” as soon as he sees the picture of Goldilocks spooning up her porridge. She may also request the same story over and over, and may pretend to read books on her own or tell you simple stories.

My son is six-months-old. Is this too young to start reading together?

It’s never too early to start. While 6 months may seem young to read to a baby, it is actually in these first months and years that early reading skills are developing. Literacy starts with a love of, and interest in, books. The goal at this age is for your son to have pleasurable and positive experiences with books so that he wants to keep learning about them. So go ahead and provide your child with chunky board books or soft cloth books that he can safely look at, chew on, and read with you. Choosing sturdy books like these means that you don’t have to say “no” or take the book away, which may build negative feelings about book play. Let him explore books in the ways he knows how right now.

My 9-month-old is so active that he doesn’t want to stop to read a book. This worries me because I know how important reading is. What can I do to get him interested?

Build book-reading and language into your child’s everyday life. Include a story, rhyme, or song as part of your child’s bedtime routine.

Use books to help your child move between activities (e.g., a book about naps before naptime, or a book about baths before bath time).

Make up rhymes or sing songs while playing with your child or driving in the car. This helps build a love of words and sounds.

Look for words to read all around you—on signs, on trucks, on food boxes and labels.

Finally, leave books where your child can reach them and let him explore them in any way he likes—even if it is only for a few seconds at a time. Don’t force him to sit or read for longer than he wants. This can lead to his having negative feelings about books.

I hear so much about how important it is to read to your baby. But my 8-month-old only seems interested in mouthing the book. Should I be stricter about us reading together, rather than just playing with the book?

Congratulations on getting your 8-month-old excited about books! Mouthing is a key way babies show interest in and explore books. Her chewing and mouthing is showing you how much she likes books.

Babies explore the world through their senses—using their eyes, hands, and mouths. Mouthing is not only normal, it’s one of the first and best ways that babies learn about the shape, size and texture of the things they see in their world. Books, with their bright colors and flapping pages, are especially interesting. Your daughter is doing all she can to learn more about these interesting and delightful square things.

I have heard conflicting opinions on speaking both French and English with my baby– some say it’s good, others say that it can delay language development. What should I do?

Go for it. Exposing your baby to both English and French will help her learn 2 languages (bilingualism) before she ever begins school. And, by providing your baby the opportunity to learn the language of your family’s culture, you are giving her a connection to her family’s roots and traditions.

There is still a lot of research to be done on childhood bilingualism. What we do know is that children can learn two or more languages during childhood without any problems. We also know that it’s often easier to learn a new language in the early years. Here are some other things that parents should keep in mind:

Babies learn at their own individual pace. Your child may develop her language skills at a different rate than a monolingual child (who is learning just one language), but it may have nothing to do with the fact that she is learning two languages at once. Further, research shows that children who are exposed to a rich bilingual language environment on a regular basis follow a similar course of language development as monolingual children.

Be consistent in how you expose your child to two languages. For example, you might speak only French to her while Dad speaks only English. Or, you speak only French in the home and English outside the home. What is important is that the language is used as part of everyday life and is not done as a “teaching” session.

Be aware that your child may develop her vocabulary at a different rate than a monolingual child. Children learning two languages at the same time may have smaller vocabularies in one or both languages compared to children learning only one language. However, when both languages are taken into consideration, bilingual children tend to have the same number of words as monolingual children. These early differences are often temporary. Usually, bilingual children catch up in their vocabulary development (if they hear both languages consistently) by the time they enter school.

And don’t worry about your child getting confused by hearing two languages. She will begin to sort it out on her own, and even sometimes use words from both languages in the same sentence. This does not mean she is mixed up! It is a very normal part of the bilingual childhood experience. So delight in the joy of hearing your child explore and learn two languages. What a gift you are giving her.

Can my newborn recognize my voice?

Even very young babies are able to recognize a familiar caregiver’s voice. In fact, research has shown that babies prefer speech to all other sounds. They enjoy hearing the different sounds, pitches, and tones that adults tend to use naturally when they talk with babies. By listening to your voice, babies develop language skills over time.

What can I do to help my 10-month-old learn to talk? I have a neighbor whose baby already says a few words!

There is a wide range for when young children start to talk. Some children say their first words at 9 months and others at 18 months. What’s most important is that your child is moving forward in her communication skills–using her sounds, gestures and facial expressions in increasingly complex ways. For example, she moves from babbling to making consonant-vowel sounds (such as da, ma, ba). She goes from grunting when she wants something to reaching towards or pointing to what she wants.

As far as what you can do, talk a lot with your baby. Talk about what you are doing while changing his diaper, dressing him, or fixing a bottle. Sing songs, and play “back and forth” games (like peek-a-boo) throughout the day. Having early “conversations” like these helps babies learn language. It can also make transitions between activities easier and relieve stress for both of you.

I keep hearing that it is really important to talk to your baby, but does my 5-month-old really understand what I am saying to him?

While young babies don’t understand the meaning of your words, early conversations help their language skills grow. When babies hear you say words over and over, the speech and language parts of the brain are stimulated. The more language they hear, the more those parts of the brain will grow and develop.

Making up stories about daily events, singing songs about the people and places your baby knows, and describing what is happening during your daily routines give babies a solid start for learning early language skills.

Babies focus on and develop language mostly because they want to connect with you. One-on-one conversations with your baby, making eye contact while you talk, and repeating back her gurgles and coos help your baby to understand how conversations work. Responding to your baby’s sounds is also important, since these are your child’s first attempts at using language. Your response motivates her to keep trying.

My one-year-old wants to hear the same story over and over, and the same lullaby every night at bedtime. Is this normal?

Telling the same stories and singing the same songs over and over may feel boring to you, but for a young child, learning happens with repetition. When you read, give each of the characters its own interesting voice. This gives your baby the chance to hear different sounds, pitches, and tones of language. It also helps babies learn how to make sounds with their own voices.

All my friends are teaching their babies sign language. They tell me how great it is, but I’m afraid signing will keep my daughter from starting to talk. What should I do?

Studies show that signing with babies who have normal hearing doesn’t appear to slow down language development. In fact, some studies indicate that it may boost language skills. However, you’ll have to learn and use the signs yourself if you want to see results.

Interestingly, one reason signing may have positive results is because parents who sign with their baby are spending more time focusing on communicating — watching their child and trying to understand what he is saying. This is something every parent can do, whether or not you decide to learn sign.

In addition, parents who sign may also be using a technique called “elaboration.” For example, when a baby makes a sign for more, the parent may say in response, You want more juice? I’ll put some more in your cup. Again, this is a great idea for all parents—whether you choose to use signs or not– because it gives babies lots of new words to hear and learn.

If you watch your baby carefully, you will see that she is signaling to you all the time. When you play a game of peek-a-boo and you stop, she reaches out and babbles to let you know she wants you to keep playing. When she raises her arms to you, she is telling you she wants you to pick her up. Responding to signals like these promotes her language skills — as well as her emotional and social development.

Source: American Speech-Hearing Association, https://www.asha.org/siteassets/public/communication-milestones-birth-to-6-months.pdf

What you can do to help

What You Can Do to Help

What you can do to support your baby’s growing language and literacy skills from 0-12 Months:

Describe her feelings and experiences. For example, when you see that she is hungry, you can say: You are nuzzling at my shirt. You’re telling me you’re hungry. Okay, your milk is coming right up! Although your baby won’t understand your words right away, your caring, loving tone of voice and actions will make her feel understood. And hearing these words over and over again will help her come to understand them over time.

Copy your baby’s sounds and encourage him to imitate you.

Put words to her sounds: I think you want to tell me about the doggy over there. Look at that doggy. Hi, doggy!

Sing songs you know, or make up songs about your baby (Happy bathtime to you, happy bathtime to you, happy bathtime, sweet baby, happy bathtime to you.) You don’t have to be on key or be good at carrying a tune. Babies don’t judge—they love hearing your voice.

Play peek-a-boo. This simple turn-taking game is good practice for how to have a conversation later on. Try hiding behind a book, a pillow or a scarf. You can also play peek-a-boo by holding your baby in front of a mirror and then moving away from your reflection. Move back in front of the mirror and say, “peek-a-boo!”

Play back-and-forth games. Hand your baby a rattle or soft ball. Then see if she will hand it back to you. See if you can exchange the toy a few times. This “back-and-forth” is practice for having a conversation later on.

Read lots of books. Reading together helps your baby develop a love of reading and a familiarity with books. Reading aloud also helps your baby’s vocabulary grow as she has many chances to hear new words and learn what they mean.

Use books as part of your baby’s daily routines. Read before naptime or bedtime. Share books made of plastic at bath time. Read a story while you are waiting for the bus. Bring books to the doctor’s office to make the time go faster.

Read with gusto. Use different voices for different characters in the stories you read your baby. Babies love when adults are silly and it makes book reading even more fun.

Let your baby “read” her own way. Your baby may only sit still for a few pages, turn the pages quickly or only want to look at one picture and then be done. She may even like to just mouth the book, instead of read it! Follow your baby’s lead to make reading time a positive experience. This will nurture her love of literacy from the start.

Repeat, repeat, repeat. Babies learn through repetition because it gives them many chances to “figure things out.” When babies tell you they are interested in a book or even in a picture in a book, give them as long as they want to look at the picture or to hear the story over and over.

Parent-Child Activities

Parent-Child Activities to Promote Language and Literacy

Make a photo album. Touch some new textures. Sing some “finger play” songs. These are songs that have hand movements to go with them. “Finger plays” help children develop muscle strength and coordination in their fingers, which helps them learn to write and draw later on. A baby favorite is Pat-a-Cake: Pat-a-cake, Pat-a-cake, Baker’s Man (clap hands together), Bake me a cake as fast as you can (pretend to stir the batter), Roll it (roll your hands over one another, as if you are rolling dough), Pat it (pat your thighs), And mark it with a B for Baby and me (draw a B in the air with your finger). Other favorites are Where is Thumbkin and The Wheels on the Bus.

What’s most important about the activities you do with your baby is that they are fun for both of you. And while you are having fun, your child is also learning. Think of a game or song your baby loves. How do you think this game might also be nurturing his growing language and literacy skills?

Helping children develop the skills to understand language.

Children who’ve developed good receptive language skills can better understand the meaning of words, form coherent sentences, follow tasks appropriately, understand verbal and written information, and communicate successfully with others.

The understanding of science correlates with their language and communication skills and ours as well. We need to be able to condense what would be like two sentences into one simple word.

Teaching receptive language skills can also begin at birth… learning to recognize, understand, and associate sounds with what we want them to notice.

We want them to eventually produce the sounds related to the names of common people, food, toys, colors, shapes, nature, actions etc. by adding them to themed baskets of three to four items or as the opportunity arrises in daily life. This is meant for essential vocabulary for communication. Understanding is dependant upon frequent repetition opportunities. My daughter and I present an object or action and repeat its name three times. Yes, no, and share are great sounds for them to le

Talk to your child or narrate what you (or you and baby) are doing so they start hearing words that you use frequently as you go about your day. Kind of how we talk to our pets…they learn what the words mean through association. The first six months babies are learning all about communication skills as well. However, you can watch them listening for a familiar words about 8-12 months.

Communication and language skills should be a paramount importance which means that it’s one of the important building blocks for all the other areas. If it’s not developed early it’s more difficult to achieve later.

Children’s language skills are connected to their overall development and can predict their educational success. As speaking and listening develops, children build foundations for literacy, for making sense of visual and verbal signs and ultimately for reading and writing. You can work towards this by providing a language rich environment full of stories, rhymes, songs and play with words that are of interest to children.

Children develop strong language skills when they are involved in playful, language-rich environments with opportunities to learn new words. Hands-on experiences encourage learning and provide a context for new words to be explored. For example, it’s easier for children to learn vegetable names when they are touching or tasting them.

Songs and rhymes offer fun ways to explore the sounds and patterns of words. Poems with actions and repetition help children listen to the structure of spoken language and explore new words.

Reading stories aloud and sharing books supports children to develop language and understand new concepts. Encouraging children to notice pictures and understand words, will strengthen their language skills and widen their vocabulary.

Non-fiction and high-quality texts such as story books, encourage children to make sense of the world around them using language. Encouraging talk when sharing books is an excellent way to support communication and language.

Children extend language with pretend play and acting out stories. By offering props and ideas you can deepen the learning. This may include imaginative play with small world resources such as dolls houses, farms or garages, open ended materials (those which can be used in more than one way) such as blocks or loose parts. You can encourage language development through creativity and problem solving during activities like:

painting

exploring

observing nature

music

How to develop receptive language skillsin your baby

Teachers and parents play an essential role in fostering receptive language skills. Here are some day-to-day strategies and activities you can use in the classroom:

Chunk verbal instructions

Breaking down instructions into simple sentences helps a child understand the instruction better. For example, instead of saying, “Put on your jacket, get your bag, and wait at the door,” say, “Put on your jacket.” Once the child has done that, follow with “Get your bag,” and finally, “Wait at the door.” Giving one instruction at a time allows the child to execute it successfully, and builds their confidence.

Read books

Ask each child to point to an object or action in a picture book; for example, say, “Point to a tree” or “Point to the person standing.” Next, read a story, re-state important parts, and then ask simple questions to determine comprehension, like “What is Peter’s favorite color?” Encourage the children to predict what might happen next. Reading also helps with developing expressive language.

Encourage play

Encourage play regularly and observe the children’s activities. Encourage them to talk about their activity by asking open-ended questions like “How did you do that?” or “Tell me about what you’re doing.” Playing games is a great way to develop listening skills as they involve following instructions. For example, research shows that the game Simon Says improves listening skills.

Use non-verbal cues

Match your instructions with non-verbal cues to strengthen your message and provide visual context. For example, when you say, “Sit down,” motion them to a chair. If you say, “Put the book on the shelf,” pick up a book and put it on the shelf as you’re speaking.

Other strategies include:

Obtain and maintain eye contact before giving an instruction

Use simple and clear language

Use visual aids like pictures and signs

Repeat instructions when necessary, and have them repeat the instructions back to you

Encourage children to ask for clarification if they forget or don’t understand the instructions

Emphasize the word you want the child to learn in different scenarios

While incorporating these strategies and activities, recording each child’s progress is a great way to keep track of their milestones—something you can do with an app like brightwheel’s daily activity report.

The bottom line

Receptive language is fundamental in child development as it’s the foundation for social and academic success. When a child understands instruction and can communicate with peers, they’re more likely to succeed in life. Promote receptive language skills by incorporating plenty of activities that encourage listening and comprehension.

Communication and Language Milestones

Communication Milestones: Birth to 6 Months

Children develop at different rates and each may meet milestones earlier or later than others, even within the same family. If your child does not meet many of the milestones, contact a certified speech-language pathologist or audiologist for an assessment

Birth to 3 Months

Quietens or smiles when you talk.

Alerts to sound.

Makes sounds that differ when happy or upset.

Makes sounds back and forth with you.

Coos and makes sounds like mmmm, oooo, and aahh.

Recognizes family members and some common objects.

Looks toward voices or people talking.

4 Months to 6 Months

Laughs and giggles.

Responds to facial expressions.

Looks at objects and follows them with their eyes.

Reacts to toys that make sounds, such as bells or music.

Vocalizes during play or with objects in their mouth.

Vocalizes various vowel sounds and ometimes combines them with a consonant, such as daaa or uumm.

Receptive Language Milestones for

Babies about 8 to 12 Months

Parents and caretakers may not be aware of the relationship of receptive language to expressive language. Expressive language is how a person uses their language to convey their thoughts, needs, and feelings using words, phrases, or sentences. Receptive language is the ability to understand another person’s words and language.

As we grow from babies into adulthood, our receptive language development propels our expressive language development. So, a child’s inability to respond to certain words or phrases may be due to their receptive language development. Therefore, it is vital that we ensure our children are progressing to and through general milestones for receptive language ability. Below are some receptive language developmental milestones to keep in mind for children 8 to 12 months old.

Video of my daughter teaching Sky’s language concepts and sign language with Sky’s new ability to stand- nine months.

Recognizes and responds to their own name when it is spoken

Understands the name for motions like stand, sit, walk etc.

Recognizes immediate family members’ names

Understands names for familiar objects

Stops when hearing “No”

Responds with gesture to “Want up?”

Waves “Bye bye”

Gives an object on request with and without visual cues

Engages in social games with gestures

Should you teach them sign language?

Baby Sign Language:

A guide for the science-minded parent

What is “baby sign language”? The term is a bit misleading, since it doesn’t refer to a genuine language. A true language has syntax, a grammatical structure. It has native speakers who converse fluently with each other.

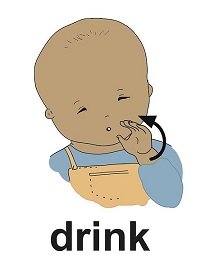

American Sign Language (ASL) and British Sign Language (BSL) are examples of genuine languages. By contrast, baby sign language, also known as baby signing, usually refers to the act of communicating with babies using a modest number of symbolic gestures. Parents speak to their babies in the usual way – by voicing words – but they also make use of these signs. For instance, a mother might voice the question, “Do you want something to drink?” while making the visual sign for “drink.”

Is baby sign language the same as ASL? Or BSL?

No, for the reasons stated above. But caregivers who teach baby sign language often use signs borrowed or adapted from the ASL or BSL lexicons.

Does baby sign language work?

The short answer is yes. It works in the sense that babies can learn to interpret and use signs. As I note below, research suggests that some babies start paying attention to signs by the age of 4 months (Novack et al 2022). By 8-10 months, they start producing signs themselves, and that can be an rewarding experience for families. But it isn’t clear that teaching babies to sign gives them any special, long-term, developmental advantages.

What about disadvantages? Does teaching babies sign language delay speech?

There isn’t a lot of research on this, but, to date, studies aren’t finding any disadvantages. For example, in an experiment that tracked babies from the age of 8 months, researchers found no evidence of any difference in language outcomes. Language development was similar whether or not babies had been exposed to signs as well as words (Kirk et al 2013).

What signs do babies learn?

It depends. In some families, parents take a “DIY” approach. They notice helpful gestures that arise naturally during conversation— iconic gestures that “act out” or resemble the things they stand for. With deliberate use of these iconic gestures — and patient repetition — their babies eventually learn to interpret these gestures as signs.

For instance, suppose you take your baby outside and find that it’s very cold. You begin talking to your baby about it, and find yourself behaving like a mime: When you say the word “cold” you act out an exaggerated shiver with your arms. If you repeat this experience multiple times, your baby may learn to regard shivering arms as a sign for “cold.” You have invented your own sign!

In the same way, your family might invent a number of additional signs — signs based on pantomiming certain actions, or representing other creatures or objects with hand movements (like holding your hands to the side of your head to depict a rabbit with long ears).

But there’s another, more standardized approach to baby sign language: teaching your baby a set of pre-existing signs from a chart, book, or video. As Lorraine Howard and Gwyneth Doherty-Sneddon (2014) note, such signs are often adapted from languages for the hearing impaired. And while some of these signs involve iconic gesturing, many others do not.

For example, consider the ASL sign for “drink.” As you can see from this illustration provided by Michael Fetters of the University of Michigan, the sign looks like you’re holding a cup to your mouth:

© 2012 Regents of the University of Michigan, created by Dr. Michael Fetters, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

It’s very iconic. If you didn’t already know what this sign is supposed to mean, you could probably figure it out. But most ASL signs aren’t like this. The gestures don’t resemble the meaning in any obvious way. You can see what I mean in these illustrations of the ASL signs for “play”, “hurt”, and “mother” or “mommy”. The mapping of signs to meanings seems arbitrary, just as is the case for most spoken words.

© 2012 Regents of the University of Michigan, created by Dr. Michael Fetters, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Does it matter if a baby sign is iconic or arbitrary?

Research suggests that it does. Babies tend to learn iconic signs more readily than arbitrary ones (Thompson et al 2012; Caselli and Pyers 2020).

However, as I argue in another article, it surely depends on an infant’s own perceptions and background knowledge. Just because a sign seems iconic to us, doesn’t mean a baby will view it’s meaning as intuitive or transparent.

For example, the ASL sign for milk resembles the act of milking a cow. That’s helpful to learners who know about the milking of cows. But if you haven’t been exposed to this knowledge (and some babies haven’t), it might look like an arbitrary sign.

So if we want to make it easier for babies to learn signs, we need to pick signs that they themselves will perceive as iconic.

Should you teach your baby signs? What are the benefits of baby sign language?

Teaching a baby to communicate using gestures can be exciting and fun. It’s an opportunity to watch your baby think and learn. The process might encourage you to pay closer attention to your baby’s attempts to communicate. It might help you appreciate the challenges your baby faces when trying to decipher language.

These are good things, and for some parents, they are reason enough to try baby signing. But what about other reasons — developmental reasons?

You’ll find many enthuastic claims online (Nelson et al 2012). Some advocates believe that baby signing programs have long-term cognitive benefits. They’ve speculated that babies taught to sign will amass larger spoken vocabularies, and even develop higher IQs.

Others have claimed that signing has important emotional benefits. They maintain that young babies may learn signs more easily than they learn spoken words, leading them to communicate more effectively at an earlier age. As a result, these infants end up experience less frustration and few temper tantrums.

Does the research support these claims?

Not exactly. But it depends on what you mean by baby-signing. If you mean “teaching babies a few, arbitrary signs as a supplement to spoken language” then there’s no compelling evidence of long-term advantages. But if you’re thinking of the more spontaneous, pantomime use of gesture, that’s a different story. There is reason to think that easy-to-decipher, iconic gesturing can help babies learn. To see what I mean, let’s take a closer look at the research.

Do baby signing programs boost long-term cognitive skills?

Overall, the evidence is lacking. The very first studies hinted that baby sign language training could be at least somewhat advantageous, but only for a brief time period (Acredolo and Goodwyn 1988; Goodwyn et al 2000).

In these studies, Linda Acredolo and Susan Goodwyn instructed parents to use signs with their infants. Then the researchers tracked the children across 6 time points, up to the age of 36 months. When the children’s language skills were tested at each time point, the researchers found that babies taught signs were sometimes a bit more advanced than babies in a control group. For instance, the signing children seemed to possess larger receptive vocabularies. They recognized more words.

But the effect was weak, and detected only for a couple of time points during the middle of the study. For the last two time points, when babies were 30 months and 36 months old, there were no statistically significant differences between groups (Goodwyn et al 2000). In other words, there was no evidence that babies benefited in a lasting way.

And subsequent studies — using stringent controls — have also failed to find any long-term vocabulary advantage for babies taught to sign(Johnston et al 2005; Kirk et al 2013; Fitzpatrick et al 2014; Seal and DePaolis 2014).

For example, Elizabeth Kirk and her colleagues (2013) randomly assigned 20 mothers to supplement their speech with symbolic gestures of baby sign language. The babies were tracked from 8 months to 20 months of age, and showed no linguistic benefits compared to babies in a control group.

And what about IQ? Although some advocates have claimed that baby sign language training boosts a child’s IQ, the relevant research has yet to appear in any peer-reviewed journal. On this question, it’s safe to say that the jury is still out.

Does signing lead to better communication? Is it true that babies can sign before they can speak?

This is an interesting idea, and it’s been championed by advocates of baby signing programs. The proposal is that babies are capable of communicating via sign language months before they are ready to communicate with spoken language. Is there compelling scientific evidence for this claim? Once again, the answer is no.

As I explain in another article, the best evidence available on the question comes from a few, small studies of children raised to sign from birth. For example, two of the most relevant studies feature samples of fewer than a dozen children for a given age range. In these studies, the average timing of first signed words appears to be a bit earlier than the average timing observed for children learning spoken language.

But there are two big problems. First, the sample sizes are just too small to draw any firm conclusions

For example, one long-term study (tracking the same babies from an early age) featured only 11 infants (Bonvillian et al 1983). Another study relies on data collected from only a few individuals each age group — for instance, just five individuals between the ages of 12 and 13 months (Anderson and Reilly 2002).

When researchers rely on such small samples, we run a high risk of getting results that are skewed: It’s relatively easy to end up with a group of individuals who aren’t representative of the population as a whole.

And this is especially true when there is a lot of individual variation, as is the case for the timing of language production. For instance, at 13 months of age, it’s normal for some children to produce as few as 4 words, while others might produce many, many more. What if — by chance — your small sample includes mostly early bloomers? Or late bloomers?

The other major difficulty concerns methodology.

We need to make sure we use similar standards when we count signs and spoken words, and different studies aren’t always comparable in this respect.

So we still have a long way to go before we can answer this question. It’s an interesting problem in many ways, so if you’d like to dig deeper, check out this Parenting Science article.

But surely there are situations where signing is easier than speaking?

I think that’s very likely. For example, the ASL sign for “spider” looks a lot like a spider. It’s iconic, which may make it easier for babies to decipher. And it might be easier for babies to produce the gesture than to speak the English word, “spider,” which includes tricky elements, like the blended consonant “sp.” The same might be said for the ASL signs for “elephant” and “deer.”

But most ASL signs aren’t iconic, and, as I explain here, some gestures can be pretty difficult for babies to reproduce — just as some spoken words can be difficult to pronounce. So it’s unlikely that a baby is going to find one mode of communication (signing or speaking) easier across the board.

What about the social and emotional benefits? Is there evidence that baby signing reduces frustration or stress?

Individual families might experience benefits. But without controlled studies, it’s hard to know if it’s really learning to sign that makes the difference. To date, claims about stress aren’t well-supported. One study found that parents enrolled in a signing course felt less stressed afterwards, but this study didn’t measure parents’ stress levels before the study began, so we can’t draw conclusions (Góngora and Farkas 2009).

Nevertheless, there are hints that signing may help some parents become more attuned to what their babies are thinking.

In the study led by Elizabeth Kirk, the researchers found that mothers who had been instructed to use baby signs behaved differently than mothers in the control group. The signing mothers tended to be more responsive to their babies’ nonverbal cues, and they were more likely to encourage independent exploration (Kirk et al 2012).

So perhaps baby signing encourages parents to pay extra attention when they communicate. Because they are consciously trying to teach signs, they are more likely to scrutinize their babies’ nonverbal signals.

As a result, some parents might become better baby “mind-readers” than they might otherwise have been, and that’s a good thing. Being tuned into your baby’s thoughts and feelings helps your baby learn faster.

But of course parents don’t need to participate in a baby sign language program to achieve these effects. The important thing is tuning into your baby, and figuring out what he or she wants. And this begs the question: Does teaching your baby signs (from ASL or other languages) necessarily give you more insight into what your baby wants?

Families can communicate quite successfully without using formal “baby signs”

© 2012 Regents of the University of Michigan, created by Dr. Michael Fetters, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

For example, consider the sign for “more,” borrowed from ASL. You bring your fingers and thumb together on each hand, and then tap your hands together by the fingertips. It’s a perfectly useful sign, and many babies have learned it. But what happens if you don’t teach your baby this sign?

Will your baby be incapable of letting you know that he wants more applesauce? Will your baby somehow fail to get across the message that she wants to play another round of peek-a-boo?

When parents pay attention to their babies — and engage them in conversation, one-on-one — they learn to read their babies’ cues. A baby might pat the table when he wants more applesauce. A baby might reach out and smile when she wants to play with you. They aren’t signs borrowed from a language like ASL, but, in context, their meaning is clear. When we respond appropriately to these spontaneous gestures, we are engaged in successful communication, and we are helping our babies build the social skills they need to master language.

This doesn’t mean there is no reason to teach formal signs!

You might find that some signs are helpful — that they allow for communication that is otherwise difficult for your baby. But it’s wrong to think of formal signs as the only gestures that matter. From the very beginnings of humanity, parents and babies have communicated by gesture. And research suggests that gestures matter. A lot!

In fact, this is so important, it’s worth considering in more detail. Whether or not you decide to teach your baby sign language, you should embrace the use of gestures when you communicate.

Why everyday gestures can have a big impact on your baby’s development

Our nonverbal cues can help babies learn language

Imagine I stranded you in the middle of a remote, isolated nation. You don’t speak the local language, and the locals don’t recognize any of your words. What would you do? Very quickly, you’d resort to pantomime. And, as you tried to learn the language, you’d soon appreciate that some people are better communicatorsthan others.

It isn’t just that they’re friendlier or more patient, though of course that helps. It’s also that they are more effective at communicating with the benefit of language. They follow your gaze, and comment on what you’re looking at. They point at the things they are talking about. They use their hands and facial expressions to act out some of the things they are trying to say. And they’re really good at it. When they talk, it’s easier to figure out what they mean.

Researchers call this ability “referential transparency,” and it helps babies as well as adults.

The evidence? Erica Cartmill and her colleagues (2013) made video recordings of real-life conversations between 50 parents and their infants – first when the babies were 14 months old, and again when they are 18 months old. Then, for each parent-child pair, the researchers selected brief vignettes – verbal interactions where the parent was using a concrete noun (like the word “ball”).

The researchers muted the soundtrack of each vignette, and inserted a beeping noise every time the parent uttered the target word. Next, they showed the resulting video clips to more than 200 adult volunteers. They asked the volunteers to guess what the parents were talking about. When you hear the beep, what word do you think the parent is saying?

The researchers were pretty tough graders. They didn’t, for example, count guesses as correct if they were too general (like guessing “toy” when the correct answer was “teddy bear”). Nor did they give volunteers credit for guesses that were too specific (guessing “finger” when the correct answer was “hand”). They also tried to eliminate vignettes where it was possible for volunteers to read the parents’ lips.

So the test wasn’t easy, and it might give us an idea of how challenging it is for babies to decipher unfamiliar words. The outcome? It turns out there was a lot of variation between parents.

There were big differences in how much referential transparency different parents offered their babies — and the most “transparent” parents had children with the most advanced language skills.

Some parents spoke with referential transparency only 5% of the time. Others were more like expert foreign language teachers, making their meanings clear up to 38% of the time.

Did the difference matter? It looks as though it might, because there were links between a parent’s referential transparency score and her child’s vocabulary three years later. Babies who had more “transparent” parents tested with larger vocabularies when they were four and half years old.

The link remained significant even after controlling for the babies’ vocabularies at the beginning of the study. And there were other interesting points too.

Although the sheer number of works spoken by parents predicted a child’s vocabulary, it was high-quality, transparent communication that mattered most.

Moreover, while researchers replicated a well-known finding – that parents of higher socioeconomic status (SES) use more words with their kids – there were no links between SES and referential transparency. Parents of high SES were no more likely than other parents to speak to their babies in a highly transparent way.

What do we make of these results?

We can’t be sure that referential transparency caused larger vocabularies. Maybe parents who scored high on referential transparency did so because they possessed a heritable trait – one they passed on to their kids – that makes people both better communicators and better verbal learners.

But remember: Parents with high referential transparency were easier for adult volunteers to understand, and these adults were unrelated to the parents. So it isn’t hard to imagine how referential transparency could lead to long-term language gains. And other research suggests that we can help our babies by being responsive to our babies’ spontaneous gestures. For example, consider the importance of pointing.

Babies learn words faster when we label the things they point at

Most babies begin pointing between 9 and 12 months, and this can mark a major breakthrough in communication. By pointing, babies can make requests (e.g., “Give me that toy”). They can also ask questions (“What is that?”) and make comments (“Look at that!”).

But the impact of this communicative breakthrough depends on our own behavior. Are we paying attention? Do we respond appropriately? As psychologists Jana Iverson and Susan Goldin-Meadow have noted, a baby who points at a new object might prompt her parent to label and describe the object. If the parent responds this way, the baby gets information at just the right moment—when she is curious and attentive. And that could have big implications for learning (Iverson and Goldin-Meadow 2005).

Experiments have confirmed the effect: Babies are quicker to learn the name of an object if they initiate a “lesson” by pointing. Andif the adult tries to initiate — by labeling an object that the baby didn’t point at? Then there is no special learning effect (Lucca et al 2018).

So there’s good reason to think that gestures affect learning. The trick is to emphasize easy-to-decipher gestures.

We want to be like that those language tutors in the remote, far-off country – the ones who respond to other people’s requests for information, and who have a knack for supplementing speech with easy-to-understand pantomime.

Does this mean that abstract, non-iconic signs pose a problem? Can baby sign language delay speech development?

That’s a reasonable question, given that baby signing programs feature signs that are non-iconic. Could the difficulty of learning such signs be a roadblock?

Studies haven’t found that babies trained to use signs suffer any disadvantages. So if you and your baby enjoy learning and using signs, you shouldn’t worry that you’re putting your baby at risk for a speech delay. In essence, you’re just teaching your baby extra vocabulary — vocabulary borrowed from a second language.

Still, it’s helpful to remember that iconic gestures are easier for your baby to figure out. For example, in one experimental study, 15-month-old toddlers were relatively quick to learn the name of a new object when the adults gestured in an illustrative, pantomime-like way. The toddlers were less likely to learn the name for an object when the spoken word was paired with an arbitrary (non-representational) gesture (Puccini and Liszkowski 2012).

What’s the takeaway?

Non-verbal communication is crucial for language development. Gestures can provide babies with important information, and help them decipher your meaning. But not all gestures are equally helpful. Research suggests that the most effective approach is

to pay attention to our babies, and respond appropriately to their spontaneous attempts to gesture and verbalize; and

to communicate with babies using a combination of speech and transparent getures — like pantomime and pointing.

In addition, I suspect it’s beneficial to build on those signs and gestures that you and your baby spontaneously invent. They already have meaning to your baby, and they are probably easier for your baby to remember.

This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t also teach your baby sign language, including some arbitrary, non-iconic signs. It can be fun and interesting, and your child might end up learning signs that are very useful. But to help your baby learn, it makes sense to emphasize gestures that are easy to decipher, and which have personal meaning to your baby.

Tips for teaching baby sign language

Whether you opt for the spontaneous, do-it-yourself approach, or you want to teach your baby gestures derived from real sign languages, keep the following tips in mind.

Tip #1: Start as early as you’d like, but remember that it will take time for your baby to learn how to make signs.

How early can you start introducing your baby to signs? If it’s enjoyable for you, there isn’t any reason to delay.

After all, babies with developmentally normal hearing begin learning about spoken language from the very beginning. They overhear their mothers’ voices in the womb, and they are capable of recognizing their mother’s native language – distinguishing it from a foreign language – at birth. Over the following months, their brains sort through all the language they encounter, and they start to crack the code. And by the time they are 6 months old, babies show an understanding of many everyday words – like “mama,” “bottle,” and “nose.” Read more about it in my article, “When do babies speak their first words?”)

So we might expect that babies are ready to observe and learn about signs at an early age — even before they are 6 months old.

In support of this idea, an experimental study found evidence that babies as young as 4 months paid close attention to a signing adult. They watched as a native user of ASL signed to them, and looked back and forth between her signs and the object she was discussing (Novack et al 2022).

But does this mean that 4-month-old babies are ready to produce signs themselves?

No, because learning to produce signs depends on the development of motor skills that 4-year-olds mostly lack. In one of those very small studies I mentioned earlier, babies didn’t produce their first sign until they were, on average, about 8.5 months old (Bonvillian et la 1983).

Tip #2:Introduce signs naturally, as a part of everyday conversation.

Babies learn words and signs by being repeatedly exposed to them, and by using them in real conversations. So let your signs come up naturally, and avoid turning these episodes into parent-driven lessons. Remember the experiments about pointing. Babies learn when they’re the ones who initiate.

Tip # 3:Keep in mind that it’s normal for babies to be less than competent. Don’t pretend you can’t understand your baby just because his or her signs don’t match the model!

Just a baby’s first attempt to say “bottle” falls short (“ba ba,”) his or her early attempts to gesture will likely be less than perfect. Baby sign language instructors call these attempts “sign approximations,” and they recommend that you run with them. In some cases, your baby might lack the fine motor skills to form the correct version of the sign.

Pretending that your baby didn’t really communicate effectively to you — because your baby’s gesture isn’t exactly what you want — is counterproductive. Don’t forget: Babies develop better language skills when their parents are tuned in and helpful!

More reading about baby communication

If you’re interested in helping your baby learn verbal skills, don’t miss by article, “How to support language development in babies.” It’s a concise round-up of the many different ways that adults can give language-learning a boost.

You can also read more about the timing of signing and speaking in this article. I review the evidence, and address misconceptions about baby sign language.

For additional information about communicating with babies, see my review of fascinating research about the effects of eye contact on infants. It discusses how shared gaze primes your baby’s brain for communication and language-learning.

And this Parenting Science article delves into the fascinating topic of “infant-directed speech,” also known as “motherese.” In cultures around the world, people naturally alter their speech patterns when addressing babies, and it looks as though these modifications help infants understand us.

Finally, if you are interested in communicating with gesture, I share you passion. Research suggests that gesture does more than help babies learn language. It can also help kids grasp mathematical concepts, and more. Read about it in this article, “The science of gestures.”

Superscript

The Importance of PLAY for Speech and Language Development

(With Tips)

“Play is often talked about as if it were a relief from serious learning. But for children play is serious learning. Play is really the work of childhood.” Fred Rogers

As quoted above play is the work of childhood. Even when your child is playing silently, they are learning important information that they will carry with them and use later. And this starts the day they are born! Those little finger plays and games of peek-a-boo really do help your child learn. As they grow and develop, they begin to learn more and more complex ideas through play.

Here are 5 ways children learn speech and language through play, from infancy on.

What, Why How by Cathy at Nurture Store. She shares how you can use random household things to inspire open ended play (comes with a free printable too!).

Here are some additional thought provoking articles on play and development.

by Erika Christakis and Nicholas Christakis on CNN.com

by Lory Hough from Harvard Graduate School of Education

by Deborah from Teach Preschool (MUST READ)

by Janet Lansbury

5 ways to add communication to your routine

Get Your Baby or Toddler Talking: 5 Ways to Add Communication to Your Daily Routine

The best thing you can do to boost your child’s language skills? Talk to them, read to them, sing to them, play with them to get your toddler talking as soon as they are ready to! The more time you spend communicating with your child, the better. Why?

From the time they’re born, kids start to develop two types of communication skills: receptive and expressive.

Receptive skills are what your child takes in (hearing and understanding).

Expressive skills are what your child puts out (sounds, gestures, and speech).

Even before baby can talk, they develop communication skills by listening to what’s going on around them. As kids get older and become more vocal, you’ll start having two-way conversations. That means more chances to sneak in receptive and expressive communication practice whenever you can.

This simple communication technique helps develop important communication skills:

Here are a few easy ways to add language play into your daily routine and encourage toddler talking.

No extra activities required!

Getting Dressed

Getting dressed is a great time to help preschool- and kindergarten-aged children practice their language skills and get your toddler talking while putting on clothes. It also helps them learn how to follow directions and organize everyday tasks. For example, they’ll learn to put a T-shirt on before their sweater and put a sweater on before their coat.

Practice receptive language skills by asking your child, “Can you go get your socks?” and telling them, “Go get your shirt.” See if they understand and remember what you’re asking. Work on expressive language by talking about their clothing. Ask your child to describe the color of their shirt.

You can also ask them to group their clothes into categories or talk about the other things they might need to wear today. When it’s cold outside, ask them what they need to wear along with their jacket — hat, scarf, gloves, etc.

Helping With Meal Time

Children can improve executive function skills (memory, self-control, and flexibility) and receptive language skills by helping set the table. Give them specific tasks and see if they can follow each of your directions.

To engage their expressive language, ask your child to describe what they’re doing and how they use each item. For example, ask, “What food can we eat with a spoon?” Make sure to keep a close eye on them, help them with heavier items (plates, empty drinking glasses), and keep sharp objects (forks, knives) out of reach.

Toddlers can also help you cook. Encourage your child to use expressive language to explain what they’re doing (pouring, stirring), and then ask them to retell the steps they took to make the meal. For example, if you make a cake, your kid can explain that first they made the batter, then they placed the batter in a dish, then dad placed the dish in the oven, and now it’s ready to eat.

Ask your child to help with one meal a day – breakfast, lunch, dinner, snack time – whichever is least stressful for you to make.

Cleaning Up Toys

Cleanup time teaches children how to follow directions and take turns. To practice turn-taking, tell your child to put away two or three specific toys and ask them which two or three toys you should put away. Purposely grab the “wrong” toy and let your child correct you. This targets their memory and expressive language skills.

Want to take it to the next level? Use cleanup time to teach kids prepositional phrases. For example, ask your child to “Put the book on the shelf” and have them repeat the phrase.

Brushing Teeth

Activities that follow a specific order, like brushing your teeth, help improve language skills, because children can retell details of the event one-by-one. Start by talking kids through everything they do to brush their teeth, from getting the toothpaste out to putting the toothbrush away. When they’re done brushing, ask them to tell you – in order – what they did.

Bath Time

Use bath time to help your child learn how to follow directions. Ask them to wash in a certain order, e.g. start with their arms, then belly, then legs. See if they can remember the order on their own. This is a great time to help your child learn about different body parts and explain what they do, e.g. ears are used for listening.

Check out your child’s communication milestones and more here!

How to create a language rich Environment

Create a Rich Language Environment for Your Child

The Importance of a Rich Language Environment

Brain development within the first year of life is pretty amazing. A baby is absorbing social skills, early literacy skills as well as developing their fine motor skills. A rich language environment will support a child’s vocabulary and even their emotional development. By offering language for the experiences we see our baby going through they are absorbing those social and emotional skills. For example, when our baby is sad because they hit their head on something, we can validate and name what they are feeling, “You hit your head, I bet that really hurts. You are sad about that.”

Like a plant growing healthily in the sunlight, a child that has access to a rich language environment develops beautifully. Language learning among babies and infants has confounded researchers for many years, with little to no agreement on what works best in raising our children to speak and understand languages well. Most research and basic behavioural observation has shown that our children imitate us to best learn the language. However, the latest research has shown that building a rich language environment greatly increases the speed and proficiency with which a child can learn a language. Here are a few tips to create a rich language environment for your child.

The Environment is as Much Mental as it is Physical

You don’t need elaborate word walls or flashcards to make your child aware of what words are. Labeling everyday objects with words will slowly help children associate the word with the object but that is more of a long-term result. Let children explore the environment around them and try to say things. Children need time to express themselves and use the language to do so, as a parent, you need to patiently listen. Let your child speak and you must listen and react to what he/she is saying.

Keep Talking

The most important source of language learning for a child is the parent. Spend a good amount of time speaking directly to your child, try to have a full conversation. Children learn by mimicking their parents as they see them the most every day. It’s not just the words that you use that are mimicked, they pick up on body language and context as well. As important as it is to learn a word and know what it means, it is even more important to know when and where to use the word. Encourage your children to express their needs and wants through their words. This will minimize the tantrums and frustrated noises that children make to try and get what they want. If your children don’t know the words for certain concepts, identify those for them and help them express these thoughts.

React and then Correct

Every time your child addresses you, the first thing you must do is respond. The response should be positive, try and smile and be open to hearing what your child has to say. Give your child your attention when they are addressing you, so they feel encouraged to talk. You can try to gently correct any mistakes later and don’t worry about them learning something new right away.

Variety and Depth

Children need to be exposed to many different words and sounds to develop and use a language. There is a window in the early development of a child’s brain, where learning language patterns and vocabulary take on an advanced level. Parents can take advantage of this fertile time by reading new words to their children. Studies have investigated how a large vocabulary (15,000 words) that have been introduced at this time to result in much smoother future learning of the language. Introducing your child to 10 words a day from the ages of 2 to 6 will help to build up that huge vocabulary.

Encourage Play and Imagination

Language learning doesn’t have to be work either, it can really take off when you play with your child. When you read a story, let your child ask all the questions that he/she wants to. Be patient and answer everything while leaving some room for the child to contribute to the answer as well. You can even start to visualize the story by drawing pictures together. Things can get even more interesting when you encourage your child to tell you a story. This role reversal can yield some funny and endearing results, with your child taking the story in many different directions. Don’t ask too many questions about why or how the story is taking place as that might stop the flow or confuse the young storyteller. Instead, tell your child what you like about the story or share small details that you think he/she might appreciate. Let your child’s imagination play as much as possible as this makes them very active and engaged in using language to further their ideas. All of this really helps with self-confidence and self-esteem.

How to raise a bilingual child

How to Raise a Truly Bilingual Child

Growing up in an environment where one or both parents are not native to the country can be confusing to children. Language, especially, tends to be a huge part of a child’s development and as we have discussed before, raising a child to be very proficient in one language takes a lot of consistent effort.

The effort can lead to some tangible benefits as well, since bilingual children have many cognitive, social and emotional experiences that single-language proficient children do not. Bilingual children routinely do better in school since they have the ability to multi-task better, their cognitive perception is faster from learning two languages and they have a unique perspective since they have the different cultural views of the two languages.

However, growing up as a bilingual speaker means that the child has to achieve a level of proficiency that approaches near-native levels. It is incredible that this expectation falls on a child, even at such an early age, but this is precisely why it is important to start early.

Starting Young Leads to Adult Proficiency

Children are much more flexible mentally when it comes to learning new concepts and language fits this mould. People say that speaking two languages confuses the child but that is not true at all.

On the contrary, starting with two languages early makes the child far more aware of the nuances and differences from a nascent stage. This benefits their brain development as well as they are effectively learning two vocabularies and different cultures that go into their languages.

For instance, if each parent wants to the child to learn their native language, then each parent must commit to speaking to the child in that language. An English-speaking parent will converse and speak in English and the Thai parent will do the same in Thai.

Language crossovers between parents are understandable but to a very large degree, the parent must be responsible for the child’s understanding of the chosen language.

It sounds more difficult than it is but in reality, it is a commitment that you make to increase your child’s bilingual aptitude.

Consider the Environment

Sending your child to English-medium education institutions means that he/she will be formally schooled in English and that will dominate their language areas. However, if you live in Thailand for the long-term, it is not a guarantee that your child’s Thai language proficiency will be naturally good.

This has the opposite effect in some cases, as your child will feel alienated from Thai society despite growing up in it. You can address this from the very beginning of the language learning by finding a way to make Thai immediately accessible on a daily basis.

Following up on our previous example, an important method for your child to learn Thai is to surround your child with Thai language cartoons, get him/her to speak to native Thais daily and find out how Thais expose their language to their children.

The key here is to develop a daily routine through which your child will always have exposure to both languages. If both parents speak English but are committed to living in Thailand for the long term, speaking English at home but encouraging Thai outside the home is a great way to approach this as well.

Formal Exposure Helps

You can actively pursue the learning of a second language for your child as well. Popularly known as ‘Saturday Schools’, the basic curriculum of these classes is get the child to speak, read and even sing another language with a group of peers.

You’ll have trained teachers working on improving the basic mannerisms, nuances and unique cultural aspects of the language with children. This happens to be a great way to give the child more than one perspective on learning the language.

So it is clear that proficiency in a language is the clear goal for any parent. We want our children to have the best path to success and if being bilingual really helps then, the work should start early. Daily routines, immediate early exposure and variety are very important to nurturing a bilingual speaker, especially because you don’t want language learning to be a task or a chore. Make learning rewarding and fun and you’ll be pleased with the progress of your bilingual child.

Ways to facilitate language for your 0-2 years old

Language and Literacy Development in 0-2 Year Olds

Your child's language skills will develop rapidly between 0- and 2-years old. Learn how you can help foster this growth. PRINT

There is possibly no greater shift in development than the advancement of language abilities from birth to three. While researchers disagree about the extent to which we come pre-wired to learn language, there is no dispute that the ability to learn to fluently speak one or more languages is a uniquely human ability that (barring another complication) we are all capable of doing. It is an amazing process to behold!

Children do not arrive in the world understanding language. It is a skill they must develop over time. However, they do arrive primed to tune in to human voices and the units that make up any of the world’s languages, including sign languages. Babies will understand language (receptive language; comprehension) before producing language themselves (productive language; language output).

Long before they utter their first word, babies are developing the necessary sub-skills for language: participating in meaningful interactions with a caregiver, making vocalizations, coordinating gestures with utterances, making word approximations, etc. The road to demonstrating a basic level of language mastery is long, about 18 months for hearing children who are not using signs for early communication. Research done on children whose parents used select American Sign Language (ASL) signs in our Signing Smart programs demonstrates significant linguistic advantages tied to strategic sign use. In fact, many of our signing babies are able to demonstrate a relatively advanced level of linguistic mastery with signs, or a combination of signs and words, by 12 months.

Of course, the best way to facilitate language development is face-to-face interactions with your child. However, utilizing online resources expands the set of interactions you and your child can have. Be sure that you are talking and interacting as you experience some language development websites, together:

Peekaboo game that rewards baby’s banging with a friendly pop-out. Hang a mobile for visual stimulation — if your child's mobile has animals, you can enhance language development by talking about them, making the animal sounds, etc.

Toddler games that you can use to get your child thinking and talking. With this game, can kids guess the animal by its eyes and sound? Can they imitate the sounds?

Baby Animals: Use animal sounds along with words and signs to help your child’s language development with cute animal photos.

Body Parts: For a fun game where your baby can just bang on the keyboard and learn parts of the face, try KiddiesGames.com.

Online Animated Stories: Simple online animated stories can be found at Fungooms.com.

Color Festival: Let your child drag the mouse across the screen making different size lines and circles. Clicking will change the color…ask your child questions and engage him as he explores this online color “playground.”

Talking Tom apps: Support your child’s talking at almost any stage with the Talking Tom series of free apps (e.g., Tom the Cat, Gina the Giraffe, Pierre the Parrot, Ben the Dog, etc.): They will repeat back any vocalization your child makes!

Animated Nursery Rhyme “games": Make nursery rhymes super fun with these simple interactives. You can foster language development and literacy as you visually engage your child in these playful experiences!

After 18 months, children’s language will typically skyrocket. Children using signs tend to have larger vocabularies than non-signers, and talk in advanced sentences. As these children expand their spoken language skills, they tend to transition fully to spoken language, with signs simply serving a clarification or learning function. There is a close relationship between children’s vocabulary and the kinds of cognitive problems they are able to solve, demonstrating how language abilities influence many aspects of learning and development.

Between the ages of 1½ and 3, grammatical markers begin to come in (e.g., -ing, plurals, articles like “the,” etc.), children begin to use prepositions such as “in” or “under,” and they use pronouns like I or you. They typically produce more and more short sentences, reaching an average of 3 words per utterance by the time they turn three. Their articulation becomes clearer, with 2/3 – 3/4 of their speech being understandable to someone outside the home by the time they are three. They begin to ask questions and the famous “why?” after every parent statement makes its appearance.

On average, 2-year-old children have a vocabulary of approximately 150-300 words, with some children’s being considerably larger. By the time they are three, their vocabulary is between 900-1000 words on average. Children continue to struggle with rhythm and fluency, as well with the volume and pitch of their voice. They begin to combine sentences with conjunctions like “and,” and they begin adding details to their descriptions. Children with larger vocabularies can more easily engage parents and the world, allowing them to extend experiences.

Continue to support your child’s language development with engaging interactions, playful reading sessions, and ad-hoc language games. For example, try to trick your child by saying incorrect information, such as telling her that lions say “woof!” See if she can correct you, and then try to trick you. Use photos and images to engage your child and invite him into conversations about family members or remembrances of past adventures. Tell your child stories about herself, real or made up. Continue talking about colors and other adjectives (big, small, etc.). Make reading an intimate time and continue to engage your child in rhymes and word play, inviting her to sing along with you. Engage her thinking by asking her what she thinks will happen next, what the character is feeling, etc.